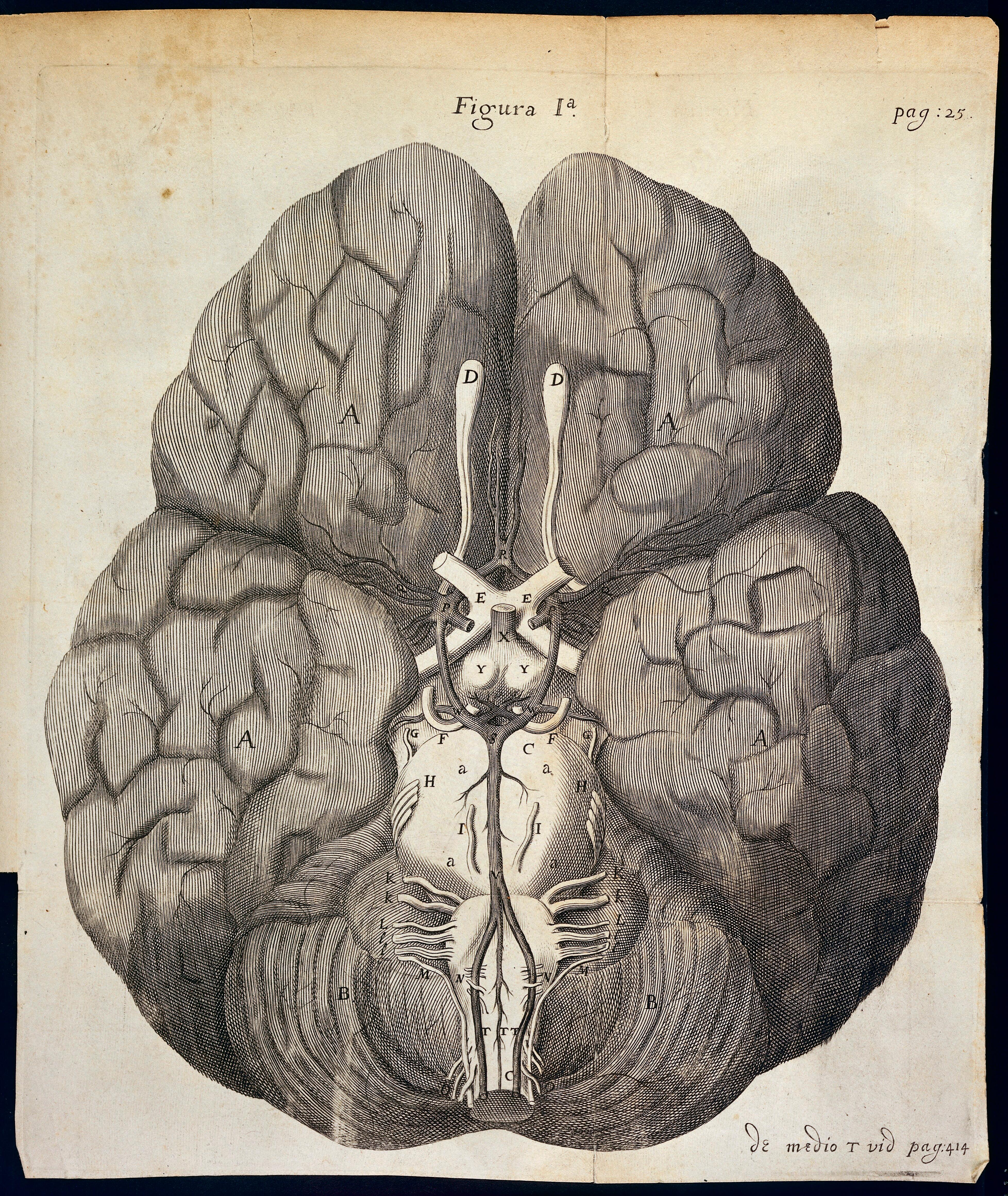

1549

Anatomy becomes part of the medical curriculum

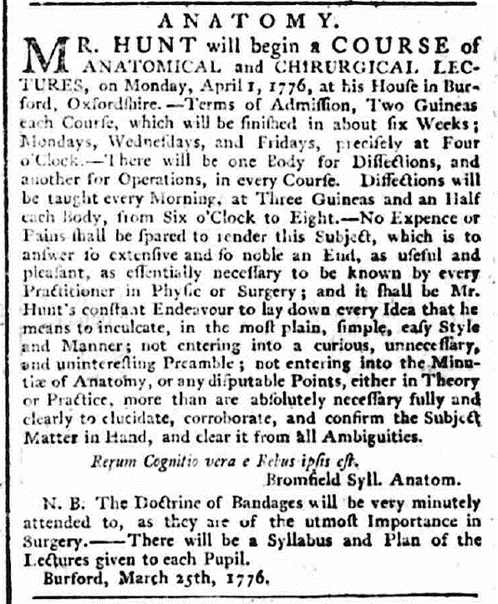

Students during the 16th century at Oxford University were required to study for at least six years to obtain a license or degree to practice medicine. However, anatomy was not a major part of their early medical education. Instead, they focused on Galenic theory and reading texts rather than practicing.

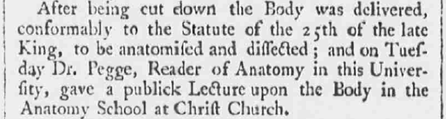

This changed after 1549, when new regulations required all students to witness two dissections during their medical studies.