Students' Mental Health

Introduction

[Trigger warning – violence]

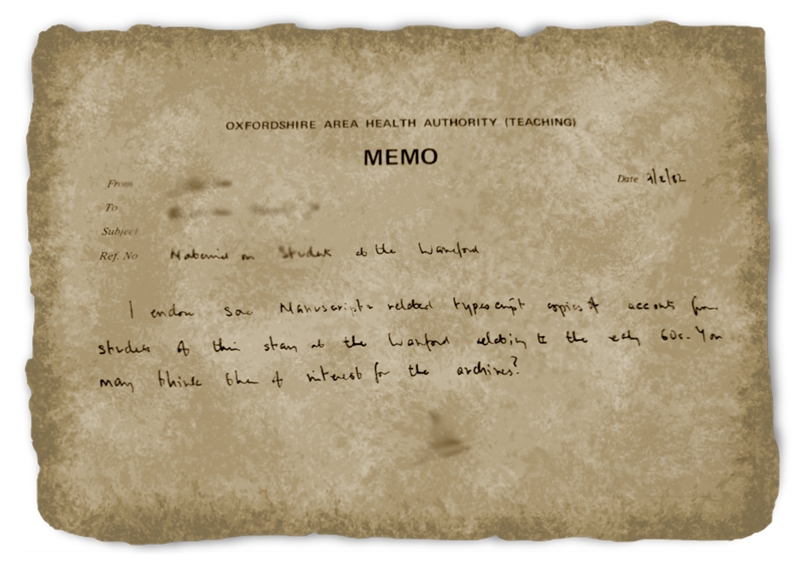

Buried in the records of Oxfordshire Health Archives lies a plain file with a short note from 1982.

"I enclose some manuscripts and related typescript copies of accounts of students of their stay at the Warneford relating to the early 60s. You may think this of interest for the archives"1

We know little about why these four particular accounts were kept or who the authors are. And yet, they are striking pieces of historical material, as four students recount first-hand the deterioration of their mental health during their years of undergraduate study at the University of Oxford in the 1960s.

The accounts speak of the jolt of confusion and displacement that came with arriving at Oxford:

I am now 23. I was 19 when I came up to Oxford. I first had psychological treatment at the end of my first year in college.

I was utterly miserable and horribly homesick.

I came up to the University a very young 18…I had embarked upon a University course for no other reason than it was ‘what I was supposed to do.2

In about April or May 1962, the year of my Final Examinations, I found that I was becoming what I then thought was extremely nervous or anxious…I was impressed with the notion that I knew very little of the material I was required to master for the examinations.3 4

Modern tabloids have often seized upon student mental health as a ‘new’ crisis, playing up the idea that young people today are less resilient and more apt to emotional crisis as the so-called ‘snowflake generation’. Historians like Sarah Crook, however, have shown that these assumptions ignore a much longer history of mental crises among undergraduate students.5

In the late nineteenth century, the idea of “overpressure” of the brain – induced by the mental strain of “cramming” (absorbing large amounts of information in a short period of time before an exam) – was increasingly concerning for doctors due to the potential long-term damage it could inflict students.

“I think it will be found that the too successful student, who has devoted his early years to constant application to books, becomes in after life a hypochondriac”, wrote Irish asylum physician Frederick McCabe in 1876 in the Journal of Mental Science.6

The twentieth century saw profound moments of change, both in the treatment of mental health and in the place of higher education within British life. In the aftermath of the second world war, university education expanded vastly. More people attended higher education, and poor mental health among students was seen as a reflection of the prospects of the country.

The dance of death. Etching by R. Dagley, 182-. Wellcome Collection.

A 1958 article from the Lancet, Britain’s leading medical journal, reveals the scale of student mental health crises in Oxford at the time.

The psychiatrist Seymour Spencer followed 100 students admitted to psychiatric hospitals in the city and found a close connection between stress from studies and the onset of their breakdowns. Close to half the students he followed had a collapse in their mental health triggered by work or exam worries. In collaboration with psychologist May Davidson, Spencer began one the earliest inpatient interventions for students, arranging for the steady stream of Oxford students who entered the Warneford to study and take their exams within the hospital.

There is increasing pressure in the first year and then increasing stress towards the finals.

Awareness and research, however, didn’t necessarily lead to the best support.

Turning back to our four student accounts stored at the archives, their experiences tell of the fragmented experience of mental health care in the mid-twentieth century. One laid blame directly with their College.

from my experience and that of many of my contemporaries….the SCR would appear to be the cause of most of the ‘breakdowns’ among students. Undergraduates are not regarded as people (despite the moral tutor system) but more so potential 1st, 2nds

and other 3rds.”8

*This refers to the grading system at the University of Oxford.

One tutor said “if I wasn’t happy at college the fault must be mine… and that there was obviously something very odd about me.9

Others were more forgiving of the Oxford system, highlighting instead already existing difficulties stemming from their home life and issues with mood that had travelled with them, only to be triggered by the intensity of University life.

However, the Colleges were often gatekeepers to access and that students were dependent upon the support particular to their College.

In fact, much innovation in formal student welfare came not from Oxford but from Oxford College of Technology, later Oxford Brookes, the second major university in the city. Oxford Brookes was a polytechnic institute and led the way in developing student welfare services.

At Brookes, chaplain Tony Tucker played a significant role in setting up one of the first student welfare services in the city. In 1969, Tucker responded to an advertisement in the Oxford Times for a Welfare Officer at the College, a role he would remain in for the next 20 years.10

Tragically, the role had been created in the wake of a student suicide.

Tucker and his colleagues quickly noticed the importance of housing for mental health. With halls of residence yet to become the norm at the College, students often lived in isolated “digs” across the city, intensifying loneliness. Tucker set up a housing association, prioritising accommodation for students with disabilities.11

Listen here to Tony Tucker:

Modern Mental Health Services

In the early 1990s, a more concerted attempt to join up student mental health services across the city occurred. Jonathan Leach, who played an important role in setting up creative-work based services at Restore, a community-based mental health initiative

in East Oxford, was foundational in setting up the Oxford Student Mental Health Network (OSMHN) in 2000. Leach completed a doctorate at Brookes, researching student mental health in the city.

Listen here to Dr Jonathan Leach:

But following a wave of student suicides in the 1990s, British universities, and particularly Oxford, found themselves under media scrutiny for their management of student welfare.12

A 1995 article in the British Journal of Psychiatry noted that, while there was an overall decline in the number of suicides occurring at the University of Oxford, they remained at a rate above the general population of the same age group.13 Leach’s work gathered observations from students across the city’s educational institutions. His research showed that while progress had been made, many of the stresses and strains caused by the culture of the University remained intact.

I think it has something to do with comparing themselves to others and feeling they are not good enough to be here… some are under huge pressure from their families, especially when they have grandparents or parents who have been to Oxford.”14

Others recognised the challenges for students coming to an institution still “soaked in elitism”.15 Critically, Leach’s work also highlighted the particular vulnerability of international students in Oxford to isolation and lack of support.16

For many who experience it, the intensities of University life; the first weeks, exams, the highs and lows of newfound friendships can leave an indelible mark. For some, it will result in significant challenges with mental health.

Renewed attention to mental health following the COVID-19 pandemic has led to uptick of initiatives at the University of Oxford; the University’s modern-day student support service is a well-oiled machine.17

But recent articles in student newspaper Cherwell have noted the continued issues around mental health, with students citing, among other things, the intensity of the eight-week term and the continued disparities in College provision of support.18

Conclusion

It is striking that these concerns differ little from those being discussed sixty years ago. Oxford is by no means unique in having a long and challenging history when it comes to student mental health. But the unique structure and identity on which

the University rests, play an implicit part in the story.

1 OHA W Add 253: "Accounts by 4 undergraduates of their treatment for depression/nervous breakdown", Oxfordshire Health Archives.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Sarah Crook, ‘Historicising the “Crisis” in Undergraduate Mental Health: British Universities and Student Mental Illness, 1944–1968’, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 2020, Vol.75 (2), p.193-220; 218.

6 Frederick MacCabe, “On Mental Strain and Overwork”, Journal of Mental Science, Vol.21 (95), p.388-402; 393.

7 S.J.G Spencer, “Academic Revoke and Failure among Oxford Undergraduates”, Lancet 1958, Vol.272 (7044), 438-440; 439.

8 OHA W Add 253: "Accounts by 4 undergraduates of their treatment for depression/nervous breakdown", Oxfordshire Health Archives.

9 Ibid.

10 Interview with Tony Tucker (4th January 2023).

11 Ibid.

12 Interview with Jonathan Leach (7th December 2022).

13 Keith Hawton et al, “Suicide in Oxford University Students, 1976–1990”, British Journal of Psychiatry (1995) Vol.166 (1), p.44-50.

14 Jonathan Leach, “Organisational responses to students’ mental health needs: social, psychological and medical perspectives”, PhD thesis (Oxford Brookes, 2004), 98.

15 Leach, 103.

16 Leach, 103.

17 Students at Oxford now offered our 24 hour online service | Togetherall

18 Lottie Sellers, “Oxford’s term structure is fuelling a mental health crisis”, Cherwell (16th March 2019)

rel="noreferrer noopener" target="_blank">Oxford's term structure is fuelling a mental health crisis - Cherwell; “JCR Presidents brand University’s mental health provisions ‘completely unsustainable’” Cherwell (6th March

2019).