Penicillin

By Chloe Williams and Lunan Zhao

"Hi, I’m Patient X. You won’t find my name in records of penicillin. Today I’m here to re-tell the story of penicillin. Let’s find out who has been telling the traditional story, and what - or who - is left out of it. I know I was..."

What is Penicillin?

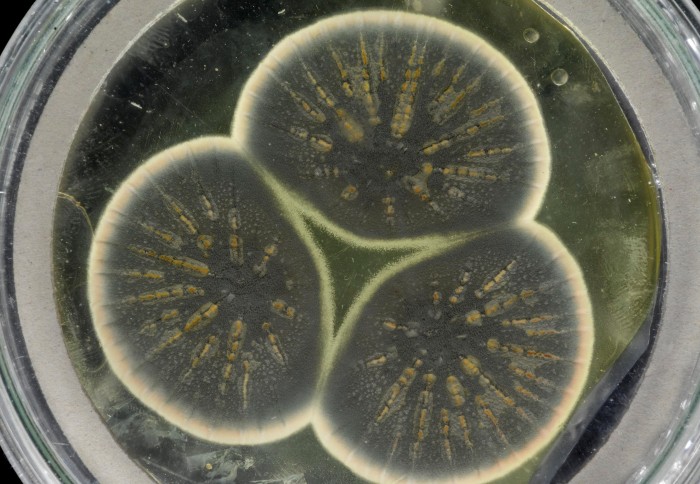

Penicillin is a medicine with antibiotic properties. It is derived from the mould of Penicillium Rubens (formerly known as Penicillium Notatum). Penicillin, and antibiotics in general, have become common across the world, used to cure infections.

Yet, what is penicillin's origins?

Let's take a look in the archives.

Click on the years below to explore the brief history of penicillin in Oxford.

University of

Oxford lab

25th May

University of

Oxford lab

The lab tests penicillin on bacterial-infected mice, who survive longer than infected mice not receiving penicillin. These studies show the promise of penicillin, but researchers know that the doses will need to be much higher for successful use in humans.

12th February

First treatment

on a human begins

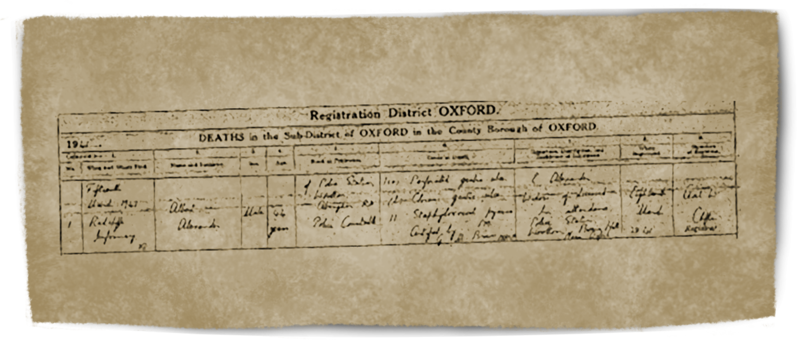

The first treatment on a human with penicillin begins at Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, on 43-year-old police officer Albert Alexander, a patient with a staphylococcal infection. After five days of treatment, the patient improved. Unfortunately, the researchers ran out of penicillin and Alexander died.

June-July

Oxford researchers Howard Florey and William Heatley visit America to gain industrial help for mass-producing penicillin.

April

Penicillin and the army

Penicillin is offered to the British army, leading to its use on wounds and in surgeries. Mobile Neurosurgical Units are introduced to the North African and Italian fronts. Oxford surgeons like Hugh Cairns play a pivotal part in this development, enabling further trials of penicillin with patients at the Units, as well as at the St. Hugh's Hospital for Head Injuries in Oxford.

1943, Winter

Focus on elucidating the chemical structure of penicillin

The focus of the research at Oxford was to elucidate the chemical structure of penicillin. Many species were found to produce the drug, but in the era of war, publication of the chemical research being done was banded in Great Britain. Instead, the results of research were shared in private channels between British and American laboratories.

Additionally, with limited supplies and many uses for the drug across the different military channels, the war-time government made decisions about who would be at the top of the list for receiving the new drug. Winston Churchill directed that penicillin be used to the best possible military advantage and sometimes soldiers with minor infections rather than those with major injuries were prioritised for treatment.

The structure of penicillin is isolated

Penicillin's structure was isolated through collaboration with X-ray crystallographer Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin. Artificial synthesis efforts began.

Background

Let’s begin with the ‘medical’ account:

Penicillin and subsequent antibiotics have become a common medicine used in both hospitals and households around the globe. Penicillin derives its name from the Latin word for ‘a painter’s brush’, due to the visual appearance of the fungi when seen under a microscope in 1928. The Sir William Dunning School of Pathology and Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford witnessed the first successful clinical trials of penicillin in 1939-1941 as a systemic chemotherapeutic agent against bacteria, kickstarting the ‘Antibiotics Era’

[Fig 1] Dunning, Hayley. ‘Genome of Alexander Fleming’s Original Penicillin Producing Mould Sequenced’, Imperial College London (24 September 2020) <https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/204713/genome-alexander-flemings-original-penicillin-producing-mould/> [accessed 12 May 2023].

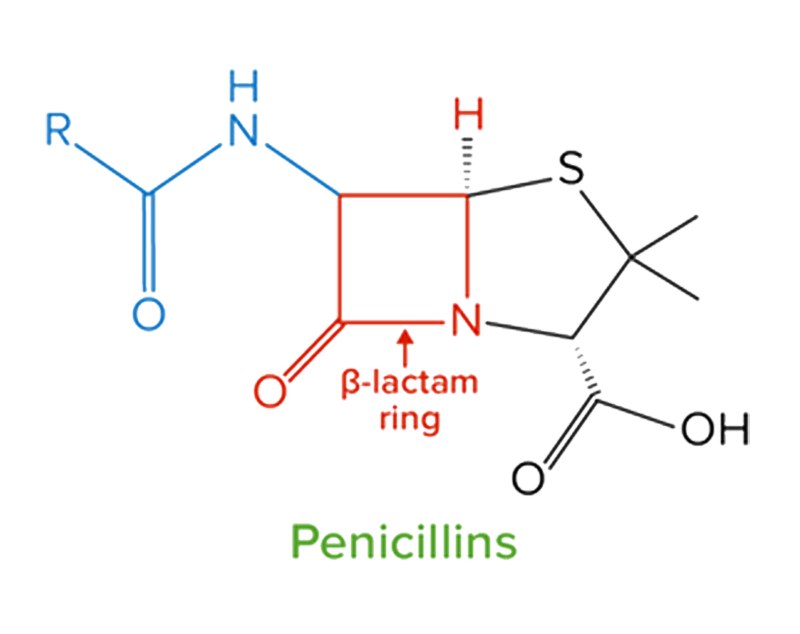

[Fig. 2] Oiseth, S., L. Jones, and E. Maza (eds.), ‘Penicillins’, Lecturio (4 Aug. 2022), <Penicillins | Concise Medical Knowledge (lecturio.com)> [accessed 12 May 2023].

This mechanism arises from the specific chemical structure of penicillin, isolated by Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin while she was working in X-Ray crystallography at Oxford in 1945. The beta-lactam ring punctures holes in bacterial cell walls.

‘Antibiotics’ is the broader term describing medications that developed after Penicillin with similar capacities to eliminate foreign harmful bacteria within humans.

So what’s the big deal about this mould? Imagine you’re me, in 1941, and got a cut on your leg while gardening, which has become infected with pus and is all red and swollen. When I went to the Radcliffe Infirmary, there were few options available. Nurses tried giving me the standard anti-microbial treatment at the time, Sulfonamides, but it was no help – the infection spread until I was barely conscious.

Then some researchers said there was a new treatment that could be tried: penicillin. Without this treatment, I likely would have died. However, lost in the these ‘medical’ narratives of progress are the perspectives of patients, lab workers, and nurses. Without us researchers could never have figured out how much to give, whether orally or via a muscle injection, for how long, or how frequently. So, who is behind the medical knowledge you take for granted today?

For the best experience to view the upcoming content, please use landscape orientation on a mobile or tablet.

Traditional Narratives

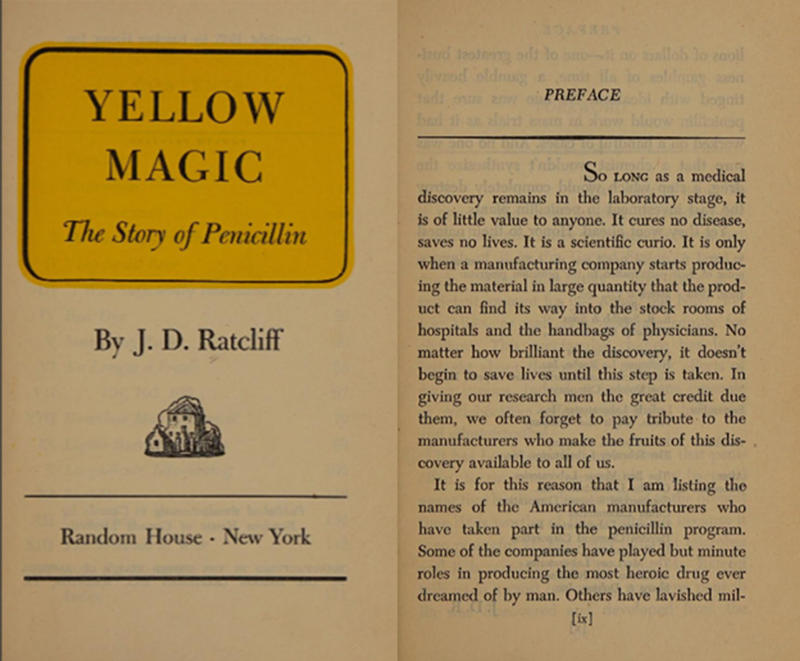

Traditional narratives are the stories that we as society recall. We envision drug manufacturers, national war efforts, prestigious scientific awards, and publications, when we discuss penicillin. The below artifacts illustrate some initial seeds of these narratives.

What is the social relevance of clinical trials?

How did penicillin translate from laboratory science to clinical practice? This book says that it is only ‘when a manufacturing company starts producing the material in large quantity’ that it can start to save lives.

[Fig 3] Ratcliff, J.D. Yellow Magic: The Story of Penicillin (New York: Random House, 1945). <Yellow magic : the story of penicillin : Ratcliff, J. D. (John Drury), 1903-1973, >[accessed 12 April 2023].

That doesn’t sound like my experience, when i was treated in the early stages of development before mass-production had started. Production had expanded dramatically in American labs only after Florey and Norman Heatley were flown to the U.S. on the Rockefeller dime, meeting representatives of Standard Oil and science and industry executives in June 1941. Oil money directly funded penicillin’s development, and it looks like it funded a lot of press telling ‘the story of penicillin’ too. Were the intentions ever purely for public good? Or were there other motives?

Who benefits from medical discoveries?

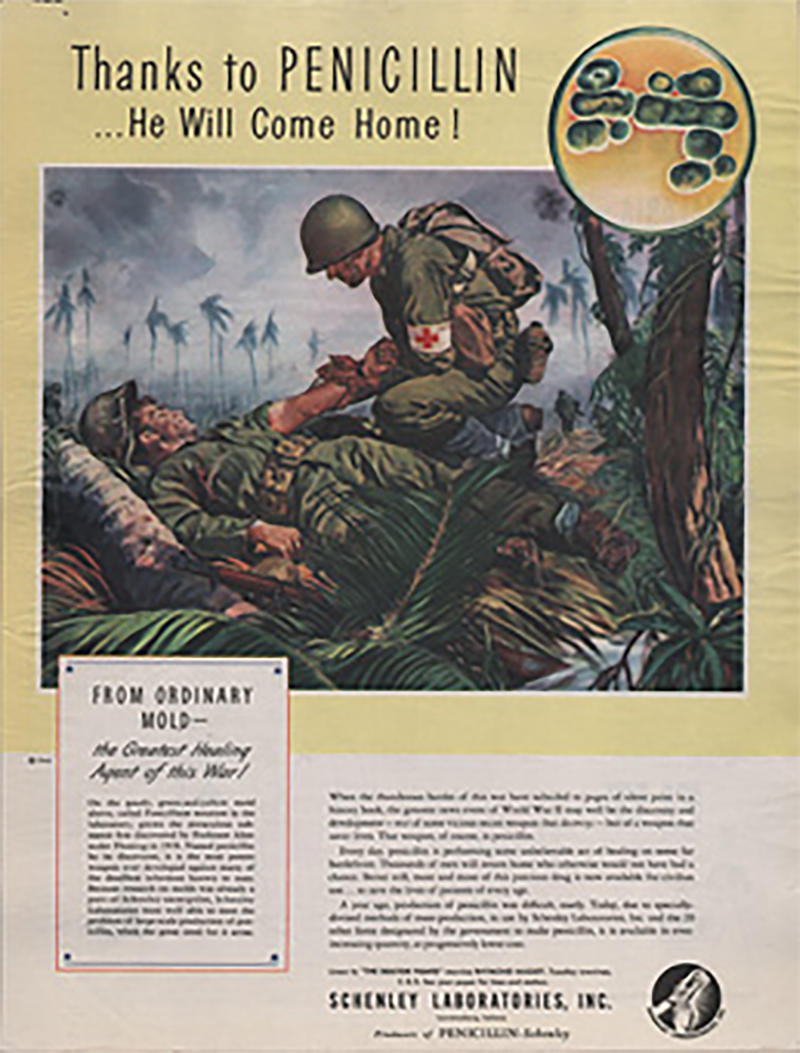

[Fig 4] The National World War II Museum Education Department, ‘”Thanks to Penicillin, He Will Come Home!” The Challenge of Mass Production’, The National World War II Museum (2017), <thanks-to-penicillin-lesson.pdf> (nationalww2museum.org) [accessed 12 April 2023].

An advertisement for penicillin - in Life magazine, fancy that! Reading this, you’d think penicillin won the war singlehandedly…well, not quite - it looks like Schenley Laboratories wants some of the credit, too. And the United States, for producing it. And Britain, for inventing it. The poster portrays a narrative of penicillin saving the common soldier, yet who truly had access? Does war or geopolitical alliance affect who has access to what medicine, when? And what happens after? We can think about the Tuskegee study which ran from 1932 to 1972. This was a 'scientific' study where a group of Black men in Tuskegee, Alabama were left untreated for syphilis (a sexually transmitted infection) so the effects could be studied. The group were never given penicillin, even experimentally, despite its availability by the 1940s, because the lives of the Black people in the study were not valued as highly as those of white people.

Who makes it into the history books?

[Fig. 5] Nobel Prize, ‘Howard Florey’, Human Accomplishment, < Human Accomplishment>, n.d. [accessed 10 May 2023]. Florey’s Nobel Prize is currently on display in the Oxford History of Science Museum.

This is Howard Florey’s Nobel Prize in the Physiology of Medicine, shared with Ernst Chain and Alexander Fleming in 1945. I wonder how they decided the recipients? Most of the people I talked to were nurses, and the only Florey I met was Ethel, Howard Florey’s wife, who came in to administer the drug, record my progress and to collect undigested bits of penicillin mould from my urine. But Howard Florey and Alexander Fleming sure liked to talk themselves up as the founders of penicillin. In fact, those great men seem to be all anybody wants to talk about...

What are the risks of testing new medicines?

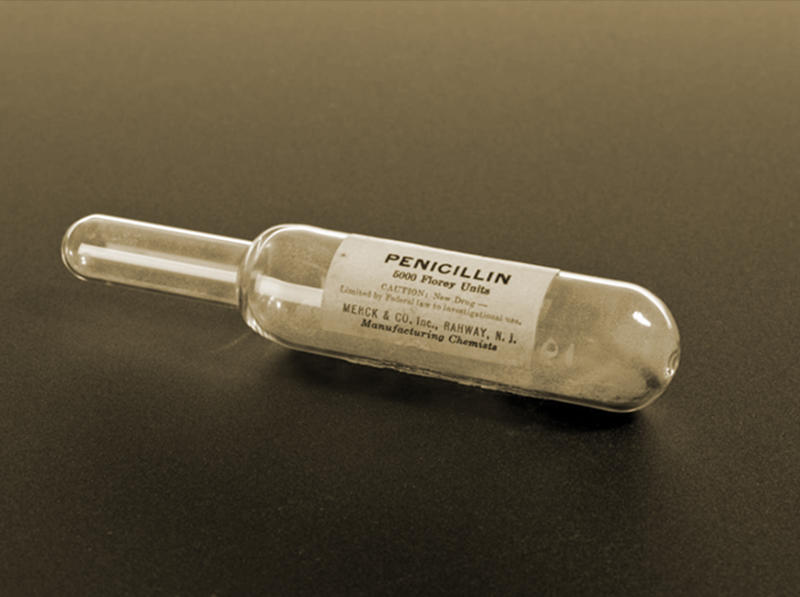

It looks like the dose of penicillin was named after those guys, too. That’s because they’re the ones at the lab who figured out the amount in each treatment - though I could tell you a little bit about that too. At first no one knew how much was enough - or too much! So it was trial and error on individuals like me. When I was treated, there was a lot of uncertainty about the side effects, and where to get more if they ran out. My second injection had a chemical impurity which caused ‘pyrexia’ - a fancy word for fever, and some rigor. Despite these side effects, penicillin cleared me up anyway, and when we ran out doctors had to get the drug I hadn’t ingested out of my urine!

[Fig. 6] Science Museum Group, ‘Glass ampoule of penicillin powder, United States, 1942-1943', Science Museum Group Collection Online, <https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co61272/glass-ampoule-of-penicillin-powder-united-states-1942-1943-penicillin>, 1964-458/1 [accessed 12 May 2023].

Nurses checked on my appetite, my fever, and asked how I was feeling, and then, through hundreds of patient experiments like mine, researchers at Florey’s Oxford lab at the William Dunning School of Pathology decided on standard numbers for doses. And that’s how we got the Florey unit - or as it was called when it was first introduced in the United States, the ‘Oxford unit’. But of course it was developed and used all over the world - during the war, my cousin was given penicillin in North Africa, and never met Florey! You can read more about his story or the first trial in the U.S. in the second folder, 'Untold Stories'.

Untold Stories

Untold Stories are the stories we have forgotten. These unravel at times the apparent coherence of traditional narratives. For instance, why do we often overlook the first patients, or the nurses and lab workers?

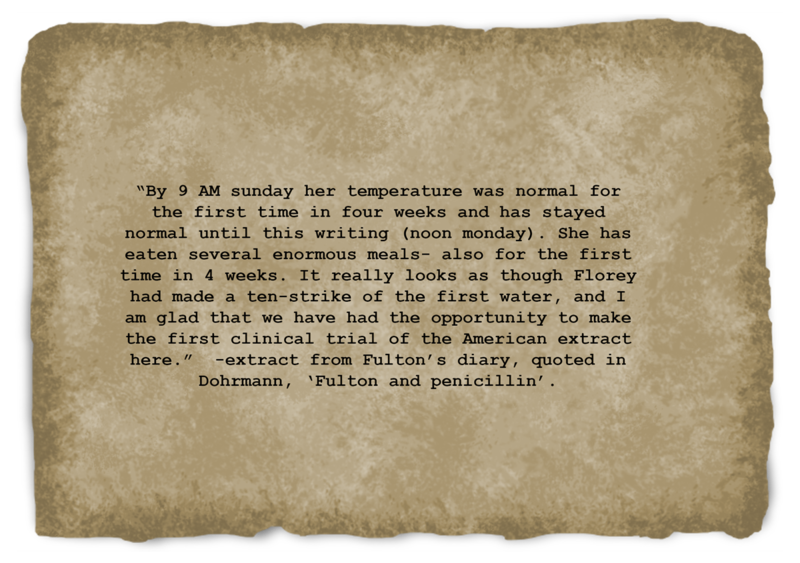

What role did patients in the US play in the story of penicillin?

The first systematic treatment in the U.S. occured in March 1942, on Anne Miller in New Haven, Connecticut. This excerpt from the diary of her doctor, Robert Fulton, sounds a lot like my experience as a patient. Appetite and temperature were closely monitored by nursing staff for several weeks. But because Mrs. Miller was in the U.S., the penicillin had to be flown in secretly - the researchers knew from cases like mine that they were onto something and were scared Nazi Germany might get a hold of the drug and use it to their advantage!

Unlike me, Mrs. Miller wasn’t chosen randomly, she was the wife of an teacher at Yale University, where Fulton worked. Fulton knew of penicillin because he was a close personal friend of Florey’s from their university days at Magdalen College, Oxford. During the war, Florey’s children even stayed with Fulton in the U.S. It looks like Fulton was very grateful for these connections and for the drug – and for the opportunity to write himself into the story of penicillin! How do you think people are chosen to partake in or benefit from medical progress today? Does everyone have equal access?

What role did patients in Oxford play in the story of penicillin?

Some patients weren’t as fortunate as Mrs. Miller and me! Police constable Albert Alexander was the first person ever to receive systematic penicillin treatment. He checked in to the Radcliffe Infirmary in January 1941 with a staph and strep infection due to lacerations sustained in an air raid. Ethel Florey discovered his condition and recommended him for the new experimental treatment. At first, he seemed to make a miraculous recovery! But because it was still an experimental treatment and hadn’t been mass produced, they ran out of the mould and sadly his infection returned to take his life.

After Alexander, Florey’s team turned towards trialling the medicine upon seriously ill children instead because they required less of the drug. How do you think researchers make ethical decisions about testing today for medical treatments that lack convincing evidence? Would you take an untested drug with low supplies, if nothing else had worked? Does it make sense to test on children if all their other treatment options have failed?

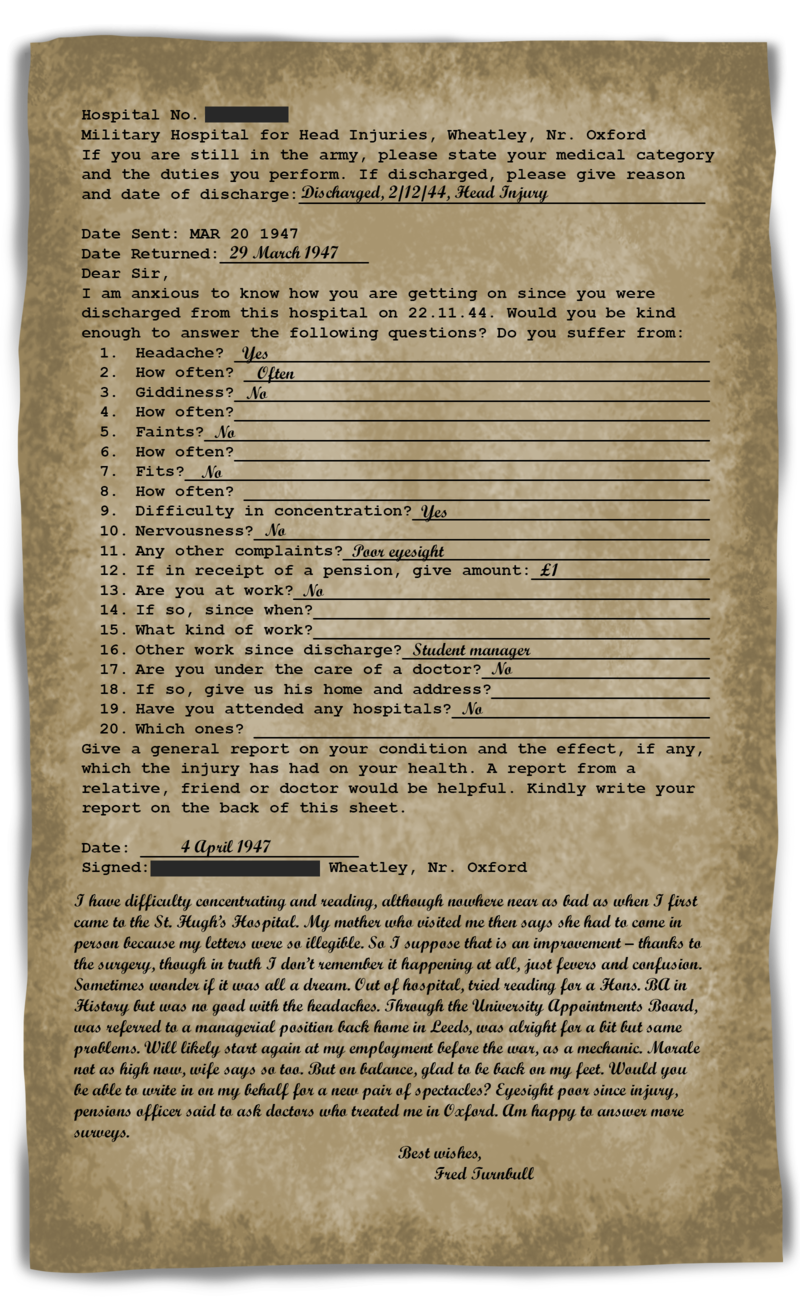

How did the Florey team connect with other developments happening in Oxford?

My cousin’s testimony shows how penicillin treatment began to expand during the war years. He sustained a shrapnel injury to his skull in North Africa and was initially treated by a Mobile Neurosurgical Unit which packed a powdered distillate of penicillin into his skull in layers. Then he was flown to St. Hugh’s College, Oxford, which was being used as a war hospital. Hugh Cairns, who had helped set up the mobile units, also supervised patients at St. Hugh’s and continued to treat infections with penicillin. For years after my cousin’s recovery, he responded to postal surveys like this one describing his progress. It sounds like he was grateful for the treatment he received - although he didn’t really know what he was being given at the time, and there was still some experimentation around how to administer the drug. I wonder if penicillin development would have been different without the war. In your era, how does war medicine differ from standard care? How do discussions of patient consent happen today? Read more about St. Hugh's Hospital here.

My cousin kept in contact with the head injury hospital until the 1980s, answering surveys like this and doing a whole range of tests. Does the story of medical treatment stop at the door of the war hospital, or do people continue to need different forms of treatment? In what circumstances do doctors have ongoing relationships with patients?

Who does the work of research?

Who actually checked on all us patients? I remember being surrounded by nursing staff. It sounds like this nurse remembers patients like me, too, and Ethel Florey who ran the ‘Pee Patrol’!

I wonder why people like nurses don’t come up so much in Florey and Fleming’s accounts, even though, as she says, her role was ‘just as important’. I wonder if there was knowledge they held that Florey may have lacked? Why does the public not discuss their contributions more? Do you think nurses could be appreciated more in hospitals today?

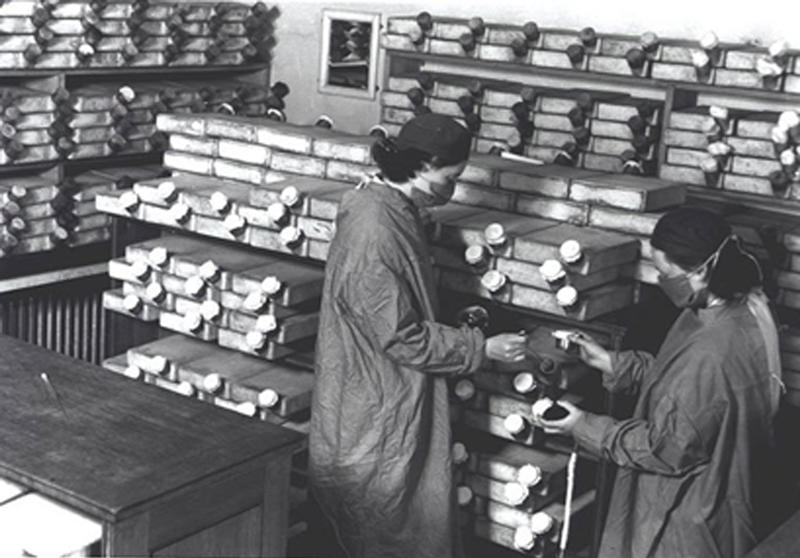

Who were the 'penicillin girls'?

I never met these ‘penicillin girls’ because they were always working in the lab. Ruth Callow, Claire Inayat, Betty Cooke, Peggy Gardner, Megan Lancaster, Patricia McKegney, and Margaret Jennings all worked at the William Dunn School of Pathology, making more of the mould culture from bedpans and reclaiming it from patient urine.

[Fig 8] Swain, K., ‘Exhibition: The penicillin girls (and guys)’, The Lancet, 389 (15 April 2017), p.1507.

I wish there was more material available to read about them, instead of all those ‘Great Men!’ Why do we not celebrate the many skilled individuals who enabled the advancement of science, but rather only the few individuals who landed their names on publications?

There’s so many more stories waiting to be told. Mine is one of many lost narratives. Some have lived on as scribbled words on yellow-paged postal surveys, held on shelves in college libraries. Some may not have been flipped through in many years. Some are so well protected by confidentiality laws that they have completely disappeared from existence. Many stories, however, live on through the fragile papers gathered here – and through you, the reader, and your questions. How do you think under-discussed historical contributions still inform modern medical practice? If you’d like to keep thinking about this question in other areas of medical practice, check out the pages on Anatomy or Mental Health or refer to these sources for more information on antibiotics and medical experimentation.

‘What Is Penicillin’?

Dunning, Hayley. ‘Genome of Alexander Fleming’s Original Penicillin Producing Mould Sequenced’, Imperial College London (24 September 2020) <https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/204713/genome-alexander-flemings-origina...

[accessed 12 May 2023].

Oiseth, S., L. Jones, and E. Maza (eds.), ‘Penicillins’, Lecturio (4 Aug. 2022), <Penicillins | Concise Medical Knowledge (lecturio.com)> [accessed 12 May 2023].

Traditional Narratives Folder

Abraham, E.P., Chain, E., Fletcher, C.M., Gardner, A.D., Heatley, N.G., Jennings, M.A., and Florey, H.W., ‘FURTHER OBSERVATIONS ON PENICILLIN’, The Lancet (British Edition) 238/6155 (1941), p.177-189. In the Gwyn MacFarlane Biographical Research

Collection: Working Papers, MS. 12387/1. Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, UK.

Chain, E., ‘Thirty years of Penicillin Therapy’ Royal College of Physicians London, 6/2 (January 1972). Gwyn MacFarlane Biographical Research Collection: Working Papers, MS. 12387/1. Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, UK.

Florey, E.M., ‘Clinical Uses of Penicillin’, British Medical Bulletin, 2/1 (1944). Gwyn MacFarlane Biographical Research Collection: Working Papers, MS. 12387/1. Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, UK.

Florey, H. W., and Abraham, E. P, ‘The Work on Penicillin at Oxford’, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences VI, Summer (1951), p. 302-317. In the Gwyn MacFarlane Biographical Research Collection: Working Papers, MS. 12387/1. Bodleian

Libraries, Oxford, UK.

Florey, E.M., Florey, H.W., and Adelaide, M.B., ‘GENERAL AND LOCAL ADMINISTRATION OF PENICILLIN’, The Lancet (British Edition) 241/6239 (1943), p. 387-397. In the Gwyn MacFarlane Biographical Research Collection: Working Papers, MS. 12387/1. Bodleian

Libraries, Oxford, UK.

Fraenkel, G.J., ‘Rockefeller, Florey and the Penicillin Connection’, Annuals of Diagnostic Pathology, 3/3 (June 1999), p.195-198.

Fraenkel, G.J., ‘Penicillin at the Beginning’, Annals of Diagnostic Pathology, 2/6 (December 1996), p.422-424.

Heatley, N., ‘H.W. Florey, Professor of Pathology and Fellow of Lincoln College, The First Ten Years, 1935-1945', 1997. ‘Sir William Dunn School of Pathology: Historical Papers’, MS. 12202/15. Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, UK.

Jorgensen‐Earp, C.R. & D. D. Jorgensen, “’Miracle from Mouldy cheese”: Chronological versus thematic self‐narratives in the discovery of penicillin’, Quarterly Journal of Speech, 88/1 (2002), p. 69-90.

Pocock, A., Portrait of Florey (1969). Gwyn MacFarlane Biographical Research Collection: Working Papers, MS. 12387/1. Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, UK.

Ratcliff, J.D., Yellow Magic: The Story of Penicillin (New York: Random House, 1945).

Science Museum Group, ‘Glass ampoule of penicillin powder, United States, 1942-1943', Science Museum Group Collection Online, <https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co61272/glass-ampou...,

1964-458/1 [accessed 12 May 2023].

The National World War II Museum Education Department, ‘”Thanks to Penicillin, He Will Come Home!” The Challenge of Mass Production’, The National World War II Museum (2017), <thanks-to-penicillin-lesson.pdf (nationalww2museum.org)> [accessed

12 April 2023].

Weatherall, M., ‘Chance and Choice in the Discovery of Drugs’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 65/4 (1972), p. 329-334.

Untold Stories Folder

Dohrmann, G J., ‘Fulton and penicillin’, Surgical neurology 3/5 (1975), p. 277-280.

‘Extracts and notes on the life and career of Albert Alexander’, 1914-2014. ‘Sir William Dunn School of Pathology: Historical Papers’, MS. 12202/15. Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, UK.

Florey, M.E.R. The Clinical Application of Antibiotics (London, New York: Oxford Medical Publications, 1952).

Fulton, J. Letter to Howard Florey concerning penicilin administration to Mrs. Miller and other patients, 17 April 1942. Gwyn MacFarlane Biographical Research Collection: Working Papers, MS. 12387/1. Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, UK.

Stone, J.L, V. Patel and J.E. Bailes, ‘Sir Hugh Cairns and World War II British advances in head injury management, diffuse brain injury, and concussion: an Oxford tale’, Journal of Neurosurgery, 125 (November 2016), p.1301-1314.

Swain, K., ‘Exhibition: The penicillin girls (and guys)’, The Lancet, 389 (15 April 2017), p.1507.

Weiner, M F, and J Silver, ‘St Hugh's Military Hospital (Head Injuries), Oxford 1940-1945', The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 47/2 (2017), p.183-189.

With thanks to Jonathan Attwood, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurology for access and aid using the military hospital ‘brain bank’ records at St. Hugh’s College, Oxford.

Drawn on in this article are: HHA 1/6/147, HHA 1/1/234, HHA 1/9/53

Workbook for secondary school students

Interested in exploring the subject more in a classroom setting? We've created a workbook with ready-to-go activities on the history of penicillin perfect for secondary school age students! Find it here.