The Case of Betty May Huffer

Betty May Huffer and the Last Days of Littlemore

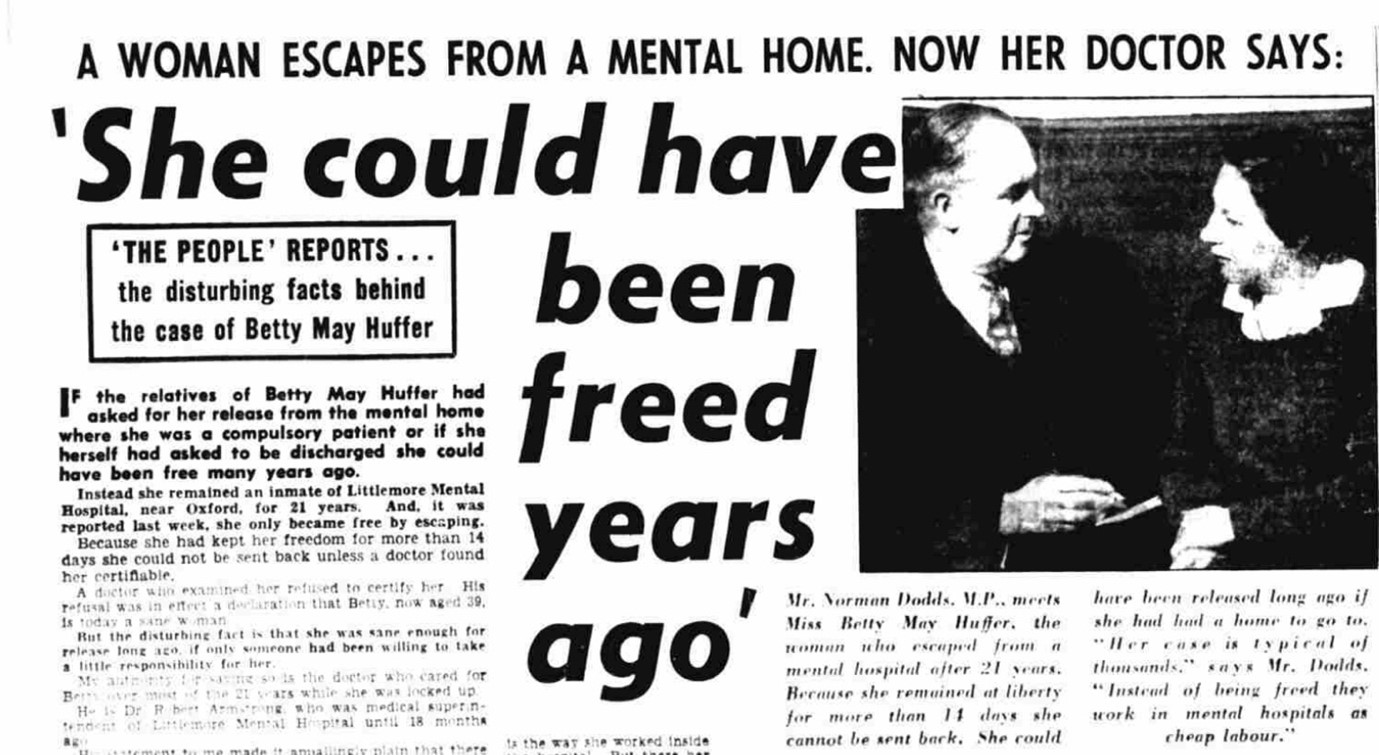

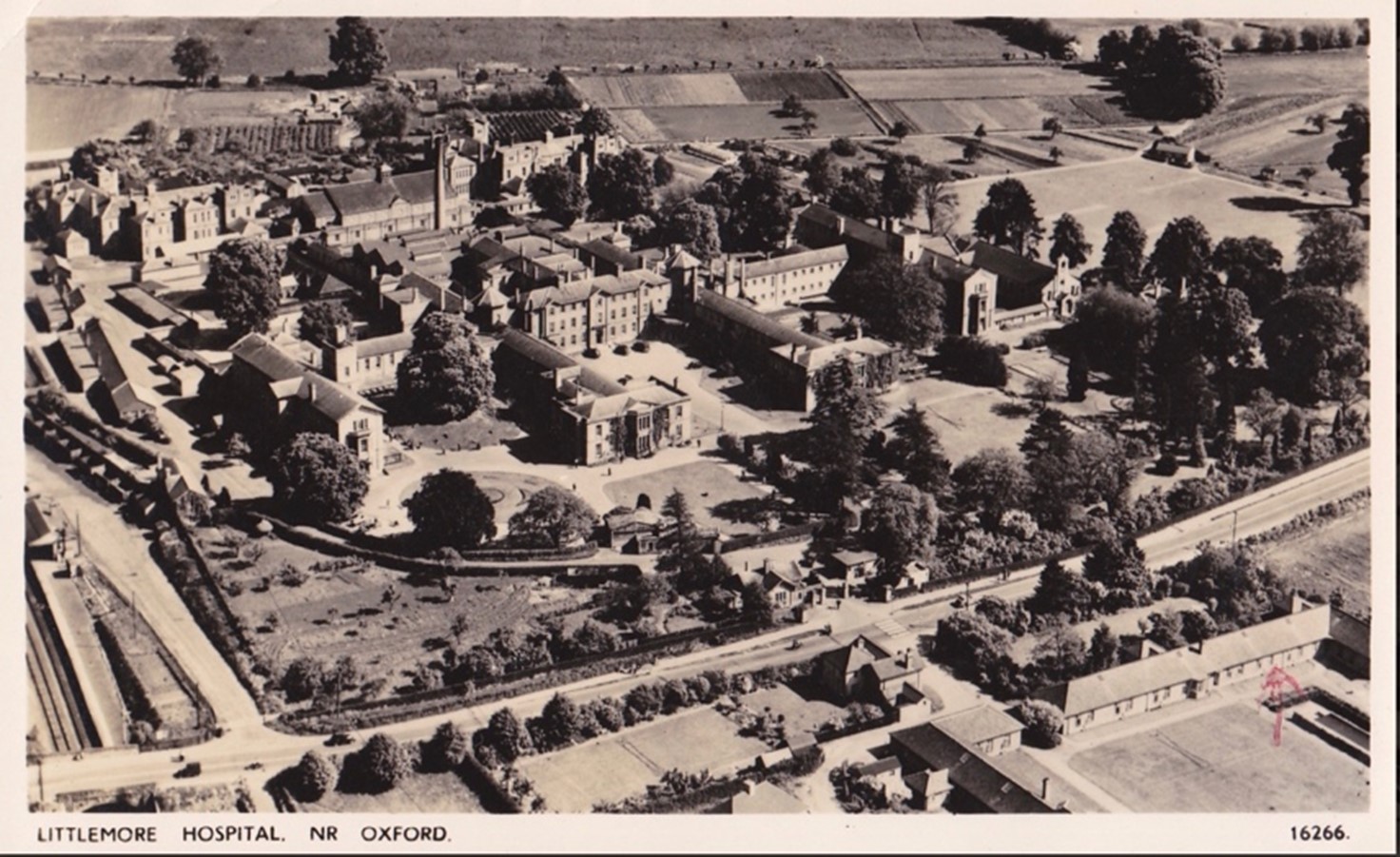

In 1960 the British tabloid The Sunday People featured a story that put both mental health and Oxford in the spotlight. The article detailed the story about Betty May Huffer, a 39-year-old woman who had ‘escaped’ from the Littlemore Psychiatric Hospital on the edges of Oxford. Born in North London, Betty had been an inmate at the Littlemore since 1938, arriving as a teenager. Young Betty had been sent to Littlemore following numerous periods at reform schools for ‘running wild’ before suffering a breakdown of sorts, which had resulted in her becoming ‘certified’ and sent to the Littlemore Hospital, which had begun life as the county’s ‘pauper’ asylum in 1846.1

‘Certified’ was a legal term which had its roots in the 1890 Lunacy Act, a piece of legislation that had introduced the requirement that those admitted to asylums must be medically certified by two doctors, as well as authored by a lay magistrate. It was introduced to help prevent wrongful confinement in asylums. However, it also meant people often only received treatment once their condition had worsened and certification could be sought.

Betty spent the next two decades inside the walls of the Oxfordshire’s largest psychiatric hospital, a vast, cavernous institute which at the turn of the twentieth century housed around eight hundred people, until one day in 1959, twenty-one years after arriving, Betty ran away. The circumstances of her escape were had elements of both the mundane and extraordinary. According to her interview with The People Betty had felt reasonably content at the Littlemore for some years. With journalist Robert Hill, she discussed feeling frightened when visiting family for holidays and wanting to return to the hospital – an inevitable consequence of institutionalisation and isolation from the wider world, and a feeling many other patients would have felt during the occasional holidays and trips they were allowed.

Betty revealed that her decision to run away was triggered by her being moved to a job in the hospital that she didn’t like. Having worked variously as a cleaner, laundress and even as a maid to one of the doctors, Betty was re-assigned to dishwashing in the canteen.

The idea that work could be used to rehabilitate mentally ill patients dated back to the nineteenth century, when it was known as ‘moral treatment’. However, commentators like Jed Boardman and Miles Rinaldi have suggested that assigning work to hospital patients was often “less about moral therapy and rehabilitation but more a matter of filling the patient’s day, reducing idleness and providing free labour for the hospital farm, kitchens and laundry, with a view to reducing costs and raising funds for the running of the institution.” 3

Alongside another patient, twenty-five-year-old labourer Gordan Pritchard, who had been at the hospital the last six months, Betty escaped.

Betty was not the first to disappear from the Littlemore and its unlikely she was the last. Stories of patients, running away from the hospital periodically appeared in the press. Her story may have remained all but lost if it had not been for an incident shortly after their escape. Huffer and Pritchard speedily exited the Oxfordshire area, travelling first to Wales and then north. In a newspaper report dated 31st October 1959, we learn of Betty and Gordon’s arrest in Cheshire for an attempted break-in. They were charged also with stealing money from an office in Merthyr Tydfil. Both were placed on remand, and following a court appearance, Betty was placed on probation.

The Mental Treatment Act of 1930 began the process of setting up outpatient clinics at psychiatric hospitals.

Betty appeared to be one of the patients still detained there by compulsion and yet her escape revealed that the original circumstances of her admission, whatever they may had been, did not align with the 39-year-old woman who unexpectedly found herself in the spotlight after her escape. The Sunday People revealed that following her capture, Betty was found to be no longer ‘certifiable’ and, since she had been at liberty for over 14 days, was not legally obliged to return to the Littlemore. Betty was free. She lived another 18 years, before dying near to where she had grown up in North London in 1978.

Betty’s story was bittersweet. The Sunday People revealed that Betty could have been “released long ago if she had had a home to go to”. Had Betty been encouraged to leave, or her family had asked for her return, release would have come much earlier. The Sunday People photographed Betty chatting with the Labour MP Norman Dodds who for some years had been campaigning to prevent wrongful detention of patients within mental hospitals. “Her case is typical of thousands” said Dodds in the piece, “instead of being freed they work in mental hospitals as cheap labour.”

MP's Win Mental Patient's Freedom (1956)

The Plea for the Silent was a series of 8 testimonies from people alleging mistreatment in mental hospitals. Dodds endorsed their accounts alongside fellow MP Dr Donald McIntosh Johnson.

Conclusion

Betty May Huffer’s story intersected with the end of an era in psychiatric treatment. The 1959 Mental Health Act set in motion the process of deinstitutionalisation and carved a slow path toward community-based models of mental

health care. But this was a lengthy process, peppered with challenges around resources, adequate housing for former long-stay patients and questions around what constituted the best path for rehabilitation, Between Betty’s

escape and Littlemore’s eventual closure in 1998, the hospital underwent profound change, particularly under the leadership of psychiatrist Bertram Mandelbrote who arrived at Littlemore the year of Betty’s escape. Under Mandelbrote,

all doors at Littlemore were unlocked, a radical step on Mandelbrote’s part that saw Littlemore receive global attention from the medical community.

Today Littlemore still stands. Like numerous other former psychiatric hospitals, it has been converted into apartments. Plant pots, bicycles and children’s toys line the doors of the building. And yet to visit, one still feels

the weight of its history. A place where some lived for decades, but which might never really be home.

1 She could have been freed years ago”, Sunday People (17th January 1960) 7.

2 Yuxin Peng, ‘Spatial Changes in an Oxford Public Asylum” Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford (2021) 213.

3 Jed Boardman and Miles Rinaldi, “Work, Unemployment and Mental Health,” in George Ikkos and Nick Bouras (eds.) Mind, State and Society: Social History of Psychiatry and Mental Health in Britain 1960–2010 330

4 “Littlemore Asylum”, The Oxford Times (11th May 1901); “Escape from Mental Hospital: Patient in Slippers leaves Littlemore”, Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette (19th October 1923).

5 “She could have been freed years ago”, Sunday People (17th January 1960) 7.

6 Ibid.

7