Managing the Plague in Early Modern Oxford

A Public Health Approach?

A physician wearing a 17th century plague preventive. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

In 1574, Oxford's high steward, Sir Francis Knollys, acknowledged that in Oxford, the ‘the university ... [was] the grounde and Cause of ye wealth of their towne, if any there be.'[1] From this quote, it is apparent that Oxford’s economy was small. Despite this, during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, Oxford experienced significant social and economic changes, reflecting broader trends across the country. Like many other towns, it saw a rise in population primarily due to economic migration. In the 1580s, the population was estimated at around five thousand. By the 1630s, it had grown to approximately ten thousand, including just over one thousand university matriculants and possibly more than five hundred university fellows.[2] A revival of trade in the local area stimulated growth within the city, and by the 1600s, cloth merchants began to dominate the city government.

Despite this growth, Oxford remained a relatively poor town. The various tax assessments suggested that even the wealthiest townsmen were far fewer and more impoverished than the leading men in Norwich, though it needs to be noted that Norwich was one of the most affluent towns in the country.[3] While Oxford was a market town and conducted considerable external trade with its leather goods and cutlery, the corporation leaders knew that its growth was still characterised by local household enterprises, dependent on local consumption centred around the university. This dependence gave the university a crucial advantage over the town, with many corporation members reliant on it for their livelihoods.

Although not wealthy, Oxford was seen as a relatively healthy city with only one severe incident: an outbreak of gaol fever in 1577 that killed three hundred.[4] The infected did not just include the prisoners but many of those who had assembled for the Assize court session and townspeople. This session had been set up to try Roland Jenks (a local bookseller) for treason for uttering treasonous words against the Queen. These words attracted the crown's attention, and the crown responded by sending various officials, including the Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer (Sir Robert Bell), to try the case. Consequently, the city was more crowded than usual as those attending the session moved between the town and the castle where the gaol was situated. This may have, therefore, accounted for an increase in infection.

John Speed's map of Oxford, 1605. Credit: Bodleian Library (in public domain).

Despite this relatively small number of outbreaks of disease, the city corporation was aware that the streets needed to be kept clean, and they attempted to do so, such as in 1582, when citizens were ordered not to ‘lay any donge, dust, ordure, rubbish, carryne in any strrets’.[5] However, apart from this incident and these complaints, the city did not face any substantial outbreaks of disease, especially the plague, until the seventeenth century.

Similar to other cities, various explanations were put forward regarding the causes. In 1603, Anthony Wood, a fellow of Oriel College, recorded that a group of citizens of Oxford complained to the University’s Convocation that the increase in plague was due to ‘the most lewd and dissolute behaviour of some base and unruly inhabitants’.[6] Wood's perspective on the causes of the plague suggests that the disease resulted from the disorder caused by certain citizens, arguing that restoring order was essential to overcoming the plague. Wood believed this could only be achieved by addressing the moral ills in society, such as poverty.[7]

The Plague Orders of 1578, the first national framework in England for dealing with infection, reflected this divided approach. The orders highlighted that the community was responsible to the infected and that the response should be generous whilst performing religious and social duties.[8] This was countered by a deep-seated belief that a breakdown of order caused the disease.[9] This can be seen within two orders. Order sixteen explains that ‘these orders should ensure that no persons of the meanest degree shall be left without succour and relief’ whilst order seventeen highlights that these orders were necessary as it was ‘natural that without national direction there will be disorder which would lead to an increase (in?) the contagion’. [10]

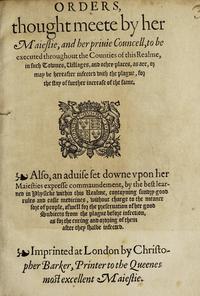

1578 Plague Orders. Source: Wellcome Collection (public domain).

Nationally, there were sporadic attempts throughout the sixteenth century to address the plague, such as a proclamation in 1550 that ordered that plague victims be separated. These attempts did not necessarily provide a national framework, and it was not until 1578 in England that central government issued national orders to manage the infection. These orders were influenced by the College of Physicians, which acted as the learned medical opinion for Elizabeth I and her government and whose advice was published alongside the plague orders.[11] This advice included how to prevent infection, which, for people experiencing poverty, was to take wormwood and put it into a pot of earth or tin. Cover it with vinegar, dip a sponge into this vinegar, and smell it.[12] For the wealthy, there were various methods they could use, including mixing wormwood and valerian with a grain of salt along with juniper berries, which had to be dried, left overnight, and then drunk the following morning.[13] The advice for the infected appears to have focused on suppositories and cordials of various berries.[14] Although this treatment might have been ineffective - the current approach to pandemics does not recommend suppositories - these orders indicated the beginnings of a more systematic approach to sickness, which tried to be preventative and reduce the spread of infection. Moreover, the 1578 orders, like COVID-19 restrictions, reflected a similar approach regarding the desire to limit movement to preserve human life and recognise the need to provide relief to those in need.[15] In 1604, these orders were reinforced by the 1604 ‘Plague Act for the Charitable Relief and Ordering of Persons Infected with the Plague' (2 James I c.31)’. The 1604 act propounds similar measures to enforce the orders as in COVID-19 which included a series of fines.

Like other cities, the Oxford civic authorities' initial response to the plague was to hope for divine intervention. The mayor is recorded as asking God for ‘health and freedome’ during this time of ‘danger and infection’.[16] However, in keeping with the national response, the Oxford civic authorities recognised that the government would need to intervene by the early seventeenth century. Hence, they pre-empted the 1604 act by introducing a limited response with the university in 1603, which resulted in the corporation levying taxes to relieve people experiencing poverty who were sick on university grounds.[17] This continued despite the 1604 act mentioning that they were prohibited from doing this. Further, the act mentions that the university was responsible for levelling this taxation on privileged persons, but records from 1605 to 1606 mention that both freemen and privileged persons were taxed together.[18] This may indicate that this agreement with the university continued, with the civic authorities taking the lead and taxing both groups.

Despite the 1578 Plague Orders and the 1604 Act, it appears that it took until 1625 for the civic authorities to provide a coordinated and comprehensive approach and implement the requirements of national legislation. This was a much more severe period of sickness, and the records mention for the first time that the corporation explicitly agreed to take responsibility for ensuring collection. The corporation minutes record that the aldermen, who also acted as the local justices, were to appoint collectors who were specifically instructed to collect the tax to relieve the sick.[19] Additionally, as the local justice, the aldermen were given the authority to decide what would be paid, demonstrating their power and responsibility in managing the crisis.[20]

In keeping with the differing views regarding public health, the corporation justified the extra taxation for relieving people experiencing poverty as needed during these dangerous times, reflecting the need for charity. Hence, the corporation minutes record the appointment of women to attend to the sick and bring out the dead as part of providing some basic treatment.[21] Moreover, there are further indications that the corporation saw its actions as serving a good and charitable purpose and protecting public welfare, especially as the initial outlay for relieving the poor and the sick had to be borrowed from the mayor.[22]

In implementing this joint agreement with the university in 1625, there are records that Ralph Wilson (an overseer whom the corporation had appointed) and John Vermally (churchwarden) prepared joint accounts and worked with the corporation, the parishes and the university to tax the colleges and record the contributions made. As requested by the Corporation, the accounts also provide the names of those who were to be relieved, including widow Harper.[23]

The corporation also imposed a quarantine following the 1604 Act, initially placing the infected with the healthy.[24] The records are silent as to the townspeople’s response to this, but in 1626, the corporation began to invest in ‘pest’ houses, which assisted in segregating the infected.[25] A sizeable investment was made in these ‘pest houses’, but they were not just used to isolate the infected population; they later accommodated people experiencing poverty.[26] As historians such as Paul Slack have mentioned, this is in keeping with their moralistic view that people experiencing poverty were considered responsible for the sickness.[27] Wood implies this as he reported that the cause of this infection was the increase in these cabins. While he does not mention that they were mainly inhabited by the poor, later corporation records, such as in 1626, highlight that these cottages could be a source of infection.[28] Moreover, the corporation minutes highlight that the initial reason for placing bailiffs at the city gate daily was to prevent strangers from entering the city, which may have included ‘vagrants’.[29] Despite this targeting people experiencing poverty for blame, Oxford Corporation displayed disgruntlement against the crown and parliament due to the plague in London, adjourning Oxford during this period. This is apparent in the council minutes when they record that they would have to finance removing St Martin’s parish church windows. Due to parliament’s men overcrowding the church, it became too hot, which increased the spread of the sickness. [30]

Furthermore, these initiatives did not go unchallenged, as the council minutes mention that some townsmen had complained they were being taxed too highly compared to other men. [31]

In examining how the corporation managed the plague infection, it is clear that Oxford's civic authorities primarily took a reactive approach to the outbreak and the associated poor relief. However, there were also elements of proactivity. The corporation ensured the involvement of all relevant agencies, notably the University, sharing responsibility for managing the infection. In assessing the public health approach of the corporation, it blended aspects of social control, primarily through quarantine orders, with an understanding that, while implementing quarantines, they also needed to provide financial relief and support.

Additionally, the plague regulations they implemented were with critics, as some townsmen complained that they were being taxed more than others. Thus, the corporation had to be realistic about how often it could continue to raise extra levies.

In summary, when examining the infection management efforts of Oxford's city corporation, the corporation played an active role in implementing the national framework. While this was not the first instance of infection management, it moved beyond sporadic local efforts by embedding the national guidelines outlined in the plague orders and the 1604 Act. Furthermore, although the civic authorities aimed to enforce compliance and maintain public order, their approach was pragmatic enough to acknowledge that their primary goal was to promote adherence to health guidelines and mitigate risks to citizens.

When analysing current health disparities highlighted by COVID-19, we can observe similarities with the approach taken during the plague, particularly in the treatment of people experiencing poverty and the practice of quarantining. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Oxford experienced significantly high levels of rough sleeping and homelessness. This, combined with instances of overcrowding, resulted in situations where healthy individuals were placed close to those infected, similar to what occurred during the plague. The overcrowding in both periods made quarantining or self-isolation often impossible or at least very challenging. [32] In contrast, though, in both periods, there were moves to address this issue, with the setting up of the ‘Everyone stays in’ program during the COVID-19 pandemic and the establishment of cabins during the plague, both of which included cooperation between the university and the city council. [33]

Glossary

City Corporation: This comprised the inner council (the council of thirteen) and the common council (which in Oxford could be as high as 90). In the early modern period, the monarch granted the corporation new powers through charters, enabling towns to achieve a certain level of self-government and independence.

Mayor: The mayor's office had links to the crown, as the confirmation of the annual election was subject to royal approval. In the sixteenth century, the mayor was also one of the local magistrates and presided over his courts. He also served as the corporation's spokesman to the outside world, serving as an 'ex officio' of several statutory commissions.

Aldermen: The aldermen were integral in dealing with cases that threatened town stability, as they could act as magistrates, which included investigating and enforcing orders inside and outside the Quarter Sessions.

[1]Alan Crossley, ‘Early Modern Oxford’, in The Victoria County History of Oxford, Volume IV: The City of Oxford, ed. by Alan Crossley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979), pp.74-181 (p. 101).

[2]Alan Crossley, ’City and University’, in The History of the University of Oxford: Volume IV,

Seventeenth-Century Oxford, ed. by Nicholas Tyacke (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), pp.

104-34 (p. 106).

[3] Crossley ‘City and University’, p. 106.: Amy Moore, Oxford Town Crown and People, 1575-1640 ( Open University: unpublished thesis , 2024), p. 26.

[4] Anthony Wood, The History and Antiquities of the University of Oxford In Two Books: Volume II, hereafter known as The Annals (Oxford: John Gutch, 1752) p. 189.

[5] OHC, Council Book A, 1523-1592. fol. 247r : Wood, The Annals, pp. 188-189.

[6] Wood, The Annals, p. 279. He does not mention which citizens made the complaint. Both the city corporation and the University had been granted charters which gave both certain rights and liberties including appointing coroners, authorising licenses and sitting as the local magistrates. Oxford city corporation governed all those who were not scholars or privileged persons (these were persons who were granted certain privileges including not having to pay civic taxes but who had not matriculated).

[7] Paul Slack, The Impact of Plague, in Tudor and Stuart England, (London: Routledge, 1985), pp. 199-200.

[8]Christopher Barker, Orders,1578? (London: 1578): Graham. Hammill,’ Miracles and Plagues: Plague Discourse as political thought ‘in Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 10 (2010) 85-104 p.101.

[9] Barker, Orders, Unnumbered.

[10] Barker, Orders, Unnumbered.

[11] Akos Tussay, ‘Plague, Discourse, Quarantine and Plague Control: 1578-125’, in Hungarian Journal of Legal Studies 61(2021), 113-132 p. 115. The orders contained the physicians advice on how to prevent the infection including when going outside to take ‘ a sweet savour in their hands, or in the corner of an handkerchief, as a sponge dipped in vinegar and rosewater mixed’, Baker, Orders, unnumbered.

[12] Rebecca Totaro, The Plague in Print: Essential Elizabethan[12]Source, 1555-1603s (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2020). p.191.: Tpbyn,’ How England first managed national infection’, p..2.

[13] Totarro, The Plague in Print, p.190.

[14]Totaro, The Plague in Print, p.191.

[15] Kara Newman ‘Shut up: Bubonic plague and Quarantine in Early Modern England’ in Journal of Social History 45 (2012), 809-834 p. 818.: OHC, Order Book 1614-1638, OCA11/2A2/1, p. 222.

[16] OHC, Council Book B, 1591-1628 OCA1/1/A1/2, fol. 287r.

[17] Wood, The Annals, pp 179-180.

[18] Wood, The Annals, pp. 279-280.

[19] OHC, Council Minutes, 1615-1634 OCA1/1/A2/2, fol. 162r.

[20] Bodl, SP/F/5, 1605-1606, Unfoliated.

[21] OHC, Council Book B, 1591-1628OCA1/1/A1/2, fol. 162r.

[22] OHC, Council Book B, 1591-1628 OCA1/1/A1/1 fol. 293r.

[23] Bodl, SP/F/3, 1625

[24] OHC, Council Minutes, 1615-1634 OCA1/1/A2/2, fol. 164v.

[25] Bodl, SP/F/5 1605-1606, Unifoliated.

[26] Bodl, SP/F/5 1605-1606, Unfoliated.

[27] Slack, The Impact of Plague, p. 291.

[28] Wood, The Annals, p. 356.

[29] Herbert Salter, and M.Hobson, Oxford Council Acts,1583-1626 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1928), p. 332.

[30] Salter, Oxford Council Acts, 1583-1626, p. 331.

[31] OHC, Council Book,1615-1634 OCA1/1/A2/2, fol. 167v. There is no record as to who these other men were but they may have been fellow parishioners who had been assessed by the churchwardens as liable for taxation but either due to the plague making collection difficult or that they had been assessed incorrectly they were not paying towards the relief needed.

[32] Bodl, SP/F/5 1605-1606, Unfoliated :Oliver Shaw, £100,000 grant for Homeless Oxfordshire amid demands for emergency homelessness law ‘ https://theoxfordblue.co.uk/100000-grant-for-homeless-oxfordshire-amid-d...

[33] Shaw, ‘£100,000 grant for Homelessness Oxfordshire’